|

|

Gwerincymru — o Gymru o’r byd |

|||

|

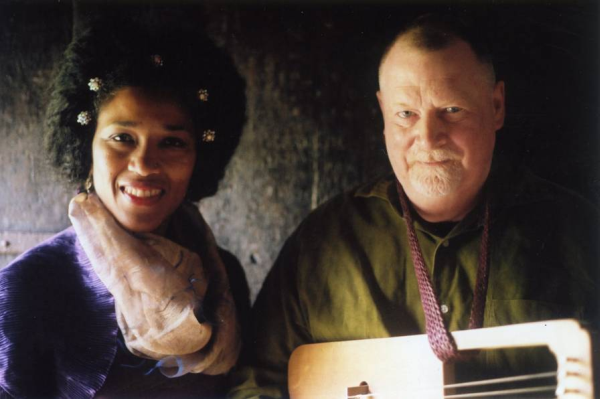

Bragod: A heady brew is coming near youby Mick Tems

It’s one of the strangest of mixes – a Welsh-speaking fiddle and crwth player from Mid Wales and a artist-singer from the West Indian island of Trinidad and Tabago, who is influenced by the age-old carnival and “jamette” traditions. They call themselves Bragod, and they gave their first public performance in October, 1999; and this autumn, they will be driving across Wales, doing a new show for universities and arts centres called Adar/Birds.

What is Bragod? Bob Evans, who is originally from Penllwyn, near Aberystwyth, but has lived in Cardiff for over 30 years, says: “Bragod means a mingled drink, like ale and wine or the wine and water of the sacrament - but as a musical term, bragodi meant to mingle flattened with natural notes to form the different tunings and modes of Welsh medieval string music or cerdd dant, in its medieval meaning.”

Bob and his partner, Mary-Anne Roberts, will be taking his crwth and her voice to the Welsh public at Chapter Arts Centre (September 7 and 8), Aberystwyth Arts Centre (October 25), Powis Hall, Bangor University (November 16), and Ucheldre Arts Centre in Holyhead (17 November). Four hundred years ago, of the very last bardic harpists, Robert Ap Huw, wrote his manuscript of 1613, the only surviving source of Welsh, bardic music. Bob said: “Bragod will mark this anniversary with a new crwth and voice performance. In our vital style we perform iconic, 14th century, Welsh poetry with the theme of birds: The Seagull and The Woodland Mass, by Dafydd ap Gwilym, set to music from the Robert ap Huw manuscript, followed by the short comic drama, Arthur's Talk With The Eagle from a 14th century manuscript.”

The apparent yawning gap between Bob’s medieval Welsh manuscripts and poetry and Mary-Anne’s interests in Trinidadian carnival and jamette traditions requires some explaining. Over to Mary-Anne: “Well, a satisfactory answer to this huge question requires a separate interview. In short, although I participated in the carnival every year, it was not until I met Ellen O'Malley-Camps, an Irishwoman who married a Trinidadian, that I became aware of its importance.

“Ellen directed performances during the carnival season featuring traditional characters, common and obscure, all seeing their last days 'on the road'. After a European tour of one of these shows in 1982, she founded the Trinidad Tent Theatre, where I trained and worked for six years. Here we learned that if we wanted to keep our traditions alive, we had to go to the practitioners and makers, who were already old people, and work with them. We met many extraordinary and generous artists, most of whom have since passed away.

“In the 18th and 19th centuries, when many of the planters and slaveowners on the island were French-speaking, the word diametre was used to describe the lower classes. It is this stratum that turned the European pre-lenten festivities, Carne Vale, into the celebration we know and export today, transformed by African elements and the experience of slavery. In our patois, diametre is pronounced jamette.

“Though there are no exact parallels, there are overlapping areas of my work as a carnival artist and revivalist and my work as part of Bragod. In the case of Trinidad carnival, there are still a very few, very old men who are in the position, were youngsters to show interest, to transmit virtually the whole richness of the tradition. In the Welsh case, medieval poetry is available in beautiful editions, but the music intended to accompany and amplify the poems has been silent for nearly four hundred years. Recent musicological scholarship has restored to us the sound of this music.

“Bragod seeks to reunite Welsh classical poetry with its contemporary Welsh music. In this we are unique. To answer the profound questions which arise in preparing to tackle this giant task, I explore the same boundless internal landscape of resources I learnt to navigate realising the archetypal characters of the Trinidad carnival.”

How did Bob and Mary-Anne meet? “Our initial meeting was through the artist, Terry Chinn, with whom I began working in 1990. We continued to meet at sessions, where I heard Bob's first airings of the crwth, playing solo and accompanying the Breton singer, Brigitte Kloareg. I was totally disarmed by the sound of the crwth.”

Bob and Mary-Anne both live in Cardiff, close to the centre. Bob’s interests in music are “early, classical, folk, World, and nearly everything.” Mary-Anne says: “I am interested in all kinds of music - folk, classical, pop, percussive, melodic, African, Indian, Japanese, Greek.”

But the most striking point is that Mary-Anne sings in word-perfect Old and Medieval Welsh. How did she absorb the language? Mary-Anne explains: “I first heard Welsh spoken when Peter Stacy and I worked together in Glasgow. We had children of the same age, and Peter spoke to his in Welsh.

“Later, Brigitte taught me choruses of Welsh folk songs, which we performed with her daughter Katell and Lynne Denman in the a capella group, San Fferian, back in the mid 90s. Performing with Bob and the crwth meant having to learn whole songs, bardic poems and ballads in Welsh. People do it all the time in community choirs and so on, memorising songs from Africa or Eastern Europe or wherever. Bob would painstakingly teach me every syllable – and, I suppose, having a tune to learn them to did help. Regarding the pronunciation of medieval Welsh, we consult the experts and have had the good fortune of learning from the likes of Dr. Dafydd Johnston, Dr. Graham Isaac, Dr. Marged Haycock and others. I absorb the language by repeating verses, learning the meaning later. The beauty and the excellent craftsmanship, particularly of the bardic material, makes this a pleasure.”

It’s my opinion that Mary-Anne’s harsh voice is a perfect foil to the rasping tone of the crwth – do Bragod agree? “Yes,” said Bob. “When Mary-Anne began singing to the crwth, she used a 'normal' voice - but that voice soon became tired. I persuaded her to sing 'like a homble be', in accordance with a 16th century Englishman's description of a Welshman's singing voice. This fell into place quite naturally, and all the acoustic phenomena produced by the crwth were immediately multiplied. Using her special voice, the vowels all produce different phenomena. This work is experimental, as is all Bragod's work. Mary-Anne experiments with other voices when I play the lyre, which has a gentler tone.”

Bob’s researches into Robert Ap Huw’s mysterious manuscripts and the ancient “code” he used are a source of fascination. He explains (all those not familiar with medieval Welsh music, please look away now): “As soon as I knew of the existence of a manuscript of late-medieval Welsh harp music, I wanted to combine the music and the poetry - cerdd dant and cerdd dafod. To this end, I began to make medieval harps, Irish and Scottish as well as Welsh. I have narrowed the scope of my project since then, though I am still very interested in poetry and music from Scotland and Ireland.

“I knew that it would not be possible to approach the problem of understanding Robert ap Huw's manuscript without the appropriate instruments. My approach is that of the historically informed music movement, that is an early music approach. This requires the use of original instruments, or good copies of them, or instruments made using drawings, good descriptions or measurements.

“The earliest sources of the musical material chosen need to be consulted and the musical ideas current before, after and during the periods being studied, in the chosen country and its neighbours. It is important to recognise that medieval Welsh music may not have sounded anything like modern Welsh folk music or classical music. I spent a great deal of time studying the manuscript in facsimile and gradually, patterns bagan to emerge. These began to make more and more sense as I learned more about European medieval music in general and about the musical ideas of ancient Greece. The binary basis of the compositions and their organisation into the 24 measures of cerdd dant together with the different tunings were probably my greatest guides.

Bob finds Ap Huw absorbing and stimulating: “The music is surprising and even shocking at times. Some of the compositions are very long. What survives, even though it is many hours of music, is only a tiny proportion of what we know to have been a huge repertoire.

“This is not polyphony, melody against a drone, a chordal accompaniment found for a melody or a single line of melody. It is music generated from the 24 measures of cerdd dant, that is the octave is divided into two sets of notes, each set corresponding to the 'I's or the 'O's of a binary pattern. Furthermore, the 'I's may be regarded as corresponding to the eternal and stable parts of the medieval universe and the 'O's to the temporal and unstable parts.

“There are two pentatonic tunings among the five warranted and established tunings, one with a semitone and one without. The remaining three of the five tunings equate to the C scale, the B flat scale and a scale with a E flat and a B natural (in my opinion). Besides these five established tunings there are many more which show an extreme playfulness on the part of the musicians who invented them. The harmonies used in the manuscript are very different from those used in modern Welsh music and indeed from those used in European art music of the same period. There is no functional harmony and no development, in the Western European sense, in this music. This music falls into place much better as soon as the instruments are tuned to Pythagorean intervals.

“Musicians search the Welsh repertoire of traditional songs and dances for an uniquely Welsh language of mode or style but in their technical aspects, those repertoires, with a very few notable exceptions, seem to be made of the same stuff as English, Irish, Scottish and Continental equivalents. To find a truly unique, home-grown body of Welsh music, with its own rigorous and philosophically based theory, a rich system of modes and tunings, a unique set of compositional bases - the music which accompanied late-medieval, high art poetry - look no further than Robert ap Huw's manuscript.”

The crwth is an inspiring instrument, says Bob: “It is tuned to the Pythagorean proportion 12:9:8:6 (4th, tone, 4th). According to Boethius, this was the tuning Orpheus used on his lyre. Using pure intervals, this small instrument can make a huge sound, full of harmonics and difference tones. When the voice is added these phenomena are multiplied. When different vowel sounds are produced by the singer, the tonal landscape seems to shift."

|

||||