MICK TEMS reviews Helen Forder’s entertaining book about Augusta Waddington’s long-lasting campaign to raise the profile of the triple harp and Welsh cultural tradition

High Hats And Harps, the fascinating and mesmerising historical biography of Lady Llanover, champion of Welsh culture and patron of the wonderful triple-harp, was published on January 10, 2013 – and, one year on, Vale of Glamorgan author Helen Forder has stirred up a maelstrom of excited talk in the popular media and in traditional circles. The good Lady has had her profile raised considerably by this former schoolteacher’s detailed and meticulous research; and a new interest has been sparked and stirred in her many activities, such as the collection of Welsh folk music, creating a series of sketches of traditional Welsh costume, requiring her estate staff to dress in Welsh uniform, employ triple-harpers and learning the Welsh language.

Even Robin Huw Bowen, number one authority and spellbinding virtuoso on the triple harp, ordered copies of Helen’s book, which is a striking title for an account. Helen has taken the trouble to dedicate her book to her mother: “for keeping alive the story of Nanny’s high hat and harp” – and, sure enough, there’s 16-year-old Nanny, Elizabeth Ann Williams, in a remarkable photograph taken at the 1886 Caerwys Eisteddfod, wearing traditional Welsh costume and a tall black hat, her triple harp leaning against her left shoulder in the traditional manner. The Llanover triple-harp team had journeyed to Caerwys to compete, their trip already grandly subsidised by Lady Llanover. Nanny’s father, Dafydd Williams (1834-1924) was under-agent at the Llanover estate, and it was this piece of family history that inspired Helen, his great-grand-daughter, to piece together the lives and times of his employers, Lord and Lady Llanover.

Helen lives in the village of Boverton, near Llantwit Major. Her main desire lay in writing a detailed account of the redoubtable Lady Llanover: “My aim in publishing this information was to draw attention to the endeavours of Lady Llanofer during the nineteenth century,” she said. “At a time when many turned from the old Welsh language and culture, she was steadfast in her enthusiasm and support for all things Welsh.”

Helen says that she preferred to use ‘Llanofer’ rather than the anglicised ‘Llanover’ except when quoting from an original source. However, she says: “Surprisingly, although Lady Llanofer persuaded her parents to use the ‘ll’ instead of the single ‘l’ in common use at the time, she did not insist on the Welsh ‘f’ rather than the English ‘v’.”

She has traced back the eventful life of Augusta Waddington through her interest in her direct-blood ancestor: “In the early 1880s, when he was appointed under-agent to Lady Llanofer, my great grandfather, David Williams, took his family from their home in Aberystwyth, to Tŷ Eos y Coed, the former Nightingale Inn, on the Llanofer Estate,” she said. “Researching my family history has resulted in my finding many Llanofer documents that mention not only my ancestors, but many of their contemporaries. “By 1891 David Williams and his family were living in Cardiff, but it is their brief time in Llanofer that intrigues me.”

It was Augusta’s desire to have her staff speak Welsh that persuaded Mr Williams to leave his Cardiganshire home and trek south to Monmouthshire. TŷEos y Coed was a direct result of one of Augusta’s more notorious campaigns. She was an outspoken and lifelong critic of the evils of alcohol, and one main interest of hers was the temperance movement. She closed all the public houses on her estate, sometimes opening a modest temperance inn in their place, such as Y Seren Gobaith (‘the Star of Hope’) temperance inn, which replaced the Red Lion at Llanellen. Closely associated with her temperance work was a form of militant Protestantism; she endowed two Calvinistic Methodist churches in the Abercarn area, with services conducted in the Welsh language, but a liturgy based on the Book of Common Prayer.

(Here’s a fascinating point: I’m a musician of Welsh dance team Gwerinwyr Gwent, and Mrs Elizabeth Murray, patron of the Lady Llanover Society and great-great-great-grand-daughter of Augusta Waddington, regularly invites us to dance at the Llanover House Open Day. We perform the Llanover Reel, a complicated and delightful dance created by Lady Llanover, who used to watch her servants stepping it up. Afterwards we make our way to The Goose And Cuckoo, a remote pub which holds the record of highest inn in Wales and which lies close to Lady Llanover’s estate, the boundaries of which end there. Although she closed many a hostelry, she could not touch The Goose And Cuckoo, which until this day serves pints of satisfying, thirst-quenching beer from its three handpumps. We even performed Llanover Reel in the shadow of The Goose And Cuckoo for the ITV evening series Great Pubs Of Wales, and comedian, presenter and real ale fan John Sparkes struggled to dance with us – but that’s another story!)

Augusta Waddington, later Lady Llanover, was born at Tŷ Uchaf in the village of Llanover (Welsh name Llanofer), four miles south from Abergavenny on March 21, 1802, the youngest of six daughters. Her parents were Benjamin Waddington and Georgina Mary Ann, from the Port family, who had moved there from Nottingham. Apart from Augusta, only Frances and Emilia survived their infancy, and Emilia died in her twenties. Augusta was 21 when she married Benjamin Hall III of Abercarn; two neighbouring large estates were joined together by this “boy and girl romance”, as Augusta was to say many years later.

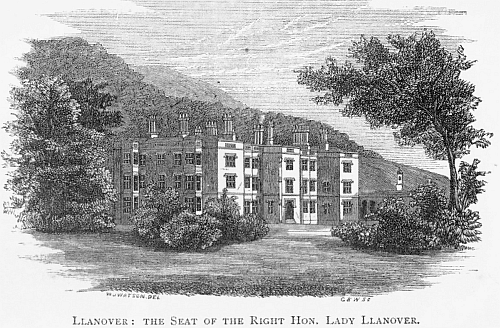

Augusta and Benjamin moved to Ty Uchaf, Llanofer, in 1828, following the death of Mr. Waddington, Augusta’s father; Augusta needed to be with her mother to comfort her in her grief. But Benjamin and Augusta shared a dream – to build a house which would become a centre for Welsh culture, a place where bards, musicians, historians and academics could come to study, exchange views, and enjoy the society of like-minded people. They commissioned Thomas Hopper to build Llys Llanover (Llanover Court) for them as a family home-cum-arts centre, and by the time it was finished in 1837, the stately building became renowned for its welcome to literary people, musicians, academics and historians. Great parties were held at Llys Llanover, where friends of the Halls stayed during the Abergavenny eisteddfodau. Christmas, as well, was a time of merriment with family, friends and tenants all joining in the festivities.

Augusta and Benjamin moved to Ty Uchaf, Llanofer, in 1828, following the death of Mr. Waddington, Augusta’s father; Augusta needed to be with her mother to comfort her in her grief. But Benjamin and Augusta shared a dream – to build a house which would become a centre for Welsh culture, a place where bards, musicians, historians and academics could come to study, exchange views, and enjoy the society of like-minded people. They commissioned Thomas Hopper to build Llys Llanover (Llanover Court) for them as a family home-cum-arts centre, and by the time it was finished in 1837, the stately building became renowned for its welcome to literary people, musicians, academics and historians. Great parties were held at Llys Llanover, where friends of the Halls stayed during the Abergavenny eisteddfodau. Christmas, as well, was a time of merriment with family, friends and tenants all joining in the festivities.

Lady Llanover collected Welsh folk music and encouraged others to do so, particularly Maria Jane Williams (1795 – 1873), whose collection The Ancient Airs of Gwent And Morgannwg won the prize in the 1837 Eisteddfod. This collection was published with Lady Llanover’s help in 1844.The Williams family of Aberpergwm were well-known to Lord and Lady Llanover, and Maria Jane (Llinos) was a particular friend of the Arglwyddes.

Benjamin Hall was born in 1802. He was for some years Member of Parliament for Monmouth, but transferred to a London seat just before to the Newport Rising in 1839, which created a troubled vortex around Monmouthshire. Big Ben, the great bell in the Westminster clock tower, was named after him, as he was Commissioner of Works in 1855 when it was built. He was created a baronet in 1838, and entered the House of Lords in 1859 under Prime MinisterPalmerston as Baron Llanover. He died in 1867.

Augusta had always been interested in Celtic Studies; her sister Frances had previously married a German ambassador to Great Britain, Baron Bunsen, whose social circle was also interested in Celtic subjects and culture. Augusta was greatly influenced by the local bard, the Rev. Thomas Price (Carnhuanawc), whom she met at Abergavenny Eisteddfod in 1826. Carnhuanawc taught her the Welsh language; she took the bardic name Gwenynen Gwent (The Bee Of Gwent). She became an early member of Cymreigyddion Y Fenni. Her Welsh was never considered fluent, but she was an extremely enthusiastic proponent of all things Welsh. She structured her household at Llys Llanover on what she considered to be Welsh traditions and gave all her staff Welsh titles and Welsh costume to wear. Her husband shared her concern for the preservation of the heritage of Wales, and campaigned for the Welsh to be able to hear church services conducted in the Welsh language.

But Helen Forder uses painstaking research to trace the history of their lives and their achievements, and she also scotches many of the myths which have grown around them. Did Big Ben really get named after Benjamin Hall, who stood at six feet seven inches? Helen deals admirably with the event, with notes of the building and casting of the bell, rubbing out all doubts with a quotation from The Times which stated that it was “proposed to call our king of bells ‘Big Ben’ in honour of Sir Benjamin Hall.”

Helen says that where women are concerned, Lady Llanover did not ‘invent’ the Welsh costume, as many people think; but she did create a Llanover ‘livery’, which is what today’s national costume seems to be based upon. She told Ceri Shaw, who interviewed her for the Americymru website: “While picturesque, the Welsh costume is not practical today, so it is hardly surprising that it is only worn at eisteddfodau and other Welsh cultural events. However, when it comes to the costume for men, one only has to look at what her family harpers had to wear to realise that costume design was not one of her talents!”

Ann Griffiths, who reviews High Hats And Harps for the Welsh American Bookstore website, says: “Then there is the myth of her hatred of the concert harp. In fact, although she employed triple harp player John Jones as her household harpist from 1836, she herself originally played the pedal harp. Helen’s book features the 1838 portrait of her twelve-year-old daughter, wearing the tall hat and Welsh costume, standing beside the Cousineau or Naderman single-action harp, which must have belonged to her mother.”

At the end of the 18th century, the rise of the more sophisticated pedal harp brought a decline in the popularity of the Welsh triple harp. The difficulty of playing on the middle row of strings during rapid passages was a drawback, as was the fact that it was impossible to play in any other key than that in which the triple harp was tuned. The famous John Thomas, Pencerdd Gwalia, intoned in The National Music Of Wales: “The pedal harp is an immense improvement in a musical sense, upon any former invention, as it admits of the most rapid modulation into every key, and enables the performer to execute passages and combinations that would not have been dreamt of previously.”

And Helen firmly lays to rest reports of a “bitter quarrel” between her and Thomas. She says that at the age of 12, John Thomas won the chief prize of a triple harp at the Abergavenny Eisteddfod of 1838. He attracted the attention of Lady Ada Lovelace, who helped him financially to attend the Royal Academy of Music in London. When Thomas was there, he abandoned the triple harp, which was played on the left shoulder and, changing shoulders, he learned to play the pedal harp, which is played on the right.

He found fame at home and abroad with his playing and his compositions. Lady Llanover encouraged him, but when she began her campaign to save the triple harp, he found he could not support her wholeheartedly, as he saw the benefits of the pedal harp and the limitations of the triple.

Helen says that Lady Llanover was angry with him, seemingly offended that he did not share her enthusiasm for promoting the triple harp; but he regretted the tension between them, saying that this had risen mainly from his ‘inability to view matters connected with his artistic pursuits in the same light as herself.’ However, he never forgot her kindness towards him at the start of his career.

However Lady Llanover, in her nineties, attended a London Welsh concert arranged by John Thomas, when she heard “20 harps played by ladies in white”. Doubtless they were pedal harps – and Helen says that perhaps more has been made of their ‘bitter quarrel’ than was true.

John Thomas had not completely abandoned the triple harp. At the Swansea Eisteddfod of 1863, he had secured sufficient money from people such as Lady Llanover, Maria Jane Williams and the Dowager Duchess of Dunraven to establish a triple harp scholarship for ten to 18-year-olds.

Throughout her long life, Lady Llanover fought to maintain all aspects of Welsh culture, which many saw as being under threat during that period. The language, literature, traditions and music of the Principality were all of interest to her, but particularly close to her heart was the plight of the triple harp; she wanted to “restore to its proper position the national instrument of the principality, and to encourage the cultivation of the pure and simple style in which the ancient Welsh music ought to be played.”

She was familiar with the harp. A harper from Caerphilly had played at her wedding in 1823, and she had lessons with the harpist and pianist Elias Parish-Alvars. She attended the Brecon Eisteddfod of 1826 and heard John Jones playing the triple harp, when his brilliant performance won him the highest award offered – the silver harp. It was at this same eisteddfod that she met Carnhuanawc, Rev Thomas Price, who was also interested in the harp and anxious to encourage the playing of the triple harp.

Following the completion of Llys Llanover in 1837, Benjamin and Augusta Hall later retained John Jones as their family harper, a position he held until his early death in 1844 at the age of 44. From then on, there was always a harper maintained by them – one of Lady Llanofer’s ways of supporting and encouraging the use of the triple harp.

Another way was through the eisteddfodau of the time; the triple harp was made the official instrument of the eisteddfodau held by Cymreigyddion Y Fenni, between 1834 and 1853, and players of the pedal harp were not allowed to take any part in the proceedings. Harps were given as prizes and, as well as donating instruments herself, Lady Llanover persuaded her wealthy and influential friends to do the same. She had a staunch ally in Carnhuanawc, who was one of the founders of Cymreigyddion Y Fenni. He too favoured the triple harp and was well aware of its plight.

More support for the triple harp was given through competitions for the instrument. There was an eisteddfod in Neath in 1866, where Thomas Gruffydd was one of the harpers. Lord Llanover gave an ‘extra’ prize of £2 ‘to the one who shall best play on the triple-stringed Harp of Wales, the old Welsh air ‘Triban Gwyr Morgannwg.’ There was a Grand Harp Contest at Llanover Court in 1869, when a musical tournament was held among the invited gentry. Lady Llanover set the rules, and two pedal harpists of the nine competitors were disqualified. John Roberts of Newtown was dissatisfied with the result of the competition, and not even the offer of £3 to himself and £1 to his son – which he refused to accept – could console him.

In 1886 the Royal Welsh Eisteddfod of Wales was held in Caerwys, “an event which has been looked forward to with no little interest on account of the historic associations of Caerwys with the congress of bards”. The harp competition was specially arranged by Lady Llanover, “who is intensely interested in these contests, and they set forth that no one would be qualified to compete who had been a player on the pedal harp the object being to restore to its proper position the national instrument of the principality, and to encourage the cultivation of the pure and simple style in which ancient Welsh music ought to be played.”

Rhes Ganol: Huw Roberts, Wynn and Steffan Thomas, Robin Huw Bowen and Rhiain Bebb Picture by Martin Roberts

Reviewer Ann Griffiths warmly praises Lady Llanover because of “her interest in the arts, music and Welsh culture, and particularly because of her championship of the triple harp. In fact, were it not for her patriotic zeal in promoting the ‘Welsh harp’, referred to scathingly by biased contemporary English critics as the ‘indigenous instrument’, our knowledge of that instrument, its players, its techniques, its traditional repertoire and its construction would have been completely lost. Our debt to her is enormous.”

Now Lady Llanover’s legacy marches on in the form of Rhes Ganol, the first such “choir” of harps since the Llanover Welsh triple harp choir, which ceased before the outbreak of the First World War. It comprises five triple harp players; Robin Huw Bowen, Rhiain Bebb, Huw Roberts, Wynn Thomas and his son Steffan. Rhes Ganol has gone from strength to strength, touring in concerts throughout Wales as well as having made many TV appearances.

The title of Helen’s book is High Hats And Harps, and its ISBN number is ISBN-10(13): 0957027834. It is published by Tallyberry Publishing, and it runs to 174 pages.

Helen’s website is http://augustaladyllanover.coffeecup.com